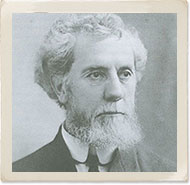

Born into a farm family but eager to find a more reliable income, Joseph Walton attends West Chester Normal School and goes immediately into teaching, eventually serving three terms as superintendent of public schools in Chester County. During his final term as superintendent (1893–1896), he is accepted as a doctoral candidate at the University of Pennsylvania. Although lacking undergraduate experience, he receives his PhD in 1896.

Walton then returns to the normal school as a history professor and is a candidate for the presidency of Swarthmore College in 1898. Instead he is hired as the principal of the Friends Central School Boys’ Department. Three years later, in 1901, he comes to George School, where his first concern is the inadequate head-of-school living arrangements. (His predecessor, George Maris, occupied disjointed quarters in Main building.) In response, the school builds Sunnybanke for $11,000, a substantial price tag for a Quaker head of school then.

Joseph inherits a school with a falling enrollment and troubled budget. Almost immediately, he crafts an audacious plan to balance the budget by expanding. Key to his plan are a new dormitory (Drayton, 1903), which removes all of the male boarding students from Main building, and a new academic building (Retford, 1906), to house classrooms formerly located in the basement and fourth floors of Main. An infirmary, swimming pool, and three faculty houses are added near the end of his term.

Joseph inherits a school with a falling enrollment and troubled budget. Almost immediately, he crafts an audacious plan to balance the budget by expanding. Key to his plan are a new dormitory (Drayton, 1903), which removes all of the male boarding students from Main building, and a new academic building (Retford, 1906), to house classrooms formerly located in the basement and fourth floors of Main. An infirmary, swimming pool, and three faculty houses are added near the end of his term.

The potentially risky expansion pays off. Although the consumer price index rises 16 percent during his tenure, the school can continue to charge $300 for boarding tuition (the original 1893 figure) by maintaining an enrollment of 230–250.

Joseph Walton also leaves a lasting imprint on George School through his development of the athletic program (fostering the “native instincts of play”) and especially the arts. Though there is already a tradition of student drama productions and a pick-up orchestra (formed in 1900, shortly after the George School Committee lifts its ban on musical instruments), he further encourages the performing arts. Drama and music thrive as extracurricular activities.

Joseph’s main contribution, however, is his promotion of the visual arts. He hunts down art to adorn the bare hallways and reception rooms of Main and creates a lending library of works for students’ rooms. The Joseph S. Walton Picture Library, numbering up to 150 pieces, exists from 1913 to 1939 and is featured in the Saturday Evening Post. He hires Louise Baker, a painting and drawing instructor who also draws Middle Eastern and Mayan archaeological finds (usually those of the University of Pennsylvania) and whose professional reputation demonstrates how seriously George School takes arts education.

While little documentation of Joseph Walton’s educational philosophy remains compared to that of his successors, his writings give a picture of his guiding principles. Walton admits the limits of teachers and textbooks, arguing, “give Mother Nature a chance and she will do more honest teaching in a week than the textbook and the ritualized teacher can do in a year.”

Joseph hesitates to enforce a strict policy of punishment for wrongdoing, instead relying on self-government. In his words, “a code of punishments for a catalog of offenses…quickly trains a bright youth to place given values on those offenses, to commit the deed, take the punishment, and pose as a hero in the eyes of his companions. He has been taught that the price of wrongdoing lies in the penalty. By such training he is unfitted for civic life.” Walton prefers that students learn to consider the moral consequences of offenses against their community.

In keeping with this philosophy, Joseph devises creative ways to handle students for whom moral consequences are not enough of a deterrent. When one boy misses meeting for worship in Newtown for several weeks, Walton goes to the presumably ill boy’s bedroom the next Sunday for a private meeting for worship. He remains for the ninety minutes it takes the other students to walk to Newtown, attend meeting, and return to campus.

After eleven years as head of school, Joseph Walton dies at fifty-seven from a duodenal ulcer. Historian Kingdon Swayne surmises that the stress of being a head compounded by the pressure of Walton’s commitment to democracy within the faculty and moral instruction in response to student wrongdoing lead to his condition and untimely demise. Despite that, Joseph’s successors follow in his philosophical footsteps, emphasizing the importance of a democratic and self-governing community.

Monastir, Tunisia, and Amman, Jordan

Monastir, Tunisia, and Amman, Jordan Irvine, CA

Irvine, CA Feasterville-Trevose, PA

Feasterville-Trevose, PA New Hope, PA (Previously NYC)

New Hope, PA (Previously NYC) Richboro, PA

Richboro, PA Englewood, NJ

Englewood, NJ Ningbo, Zhejiang, China

Ningbo, Zhejiang, China Willingboro, NJ

Willingboro, NJ Yardley, PA

Yardley, PA Newtown, PA

Newtown, PA Holicong, PA

Holicong, PA Newtown, PA

Newtown, PA Hamilton, NJ

Hamilton, NJ Yardley, PA

Yardley, PA Lambertville, NJ

Lambertville, NJ Chongqing, China

Chongqing, China Pennington, NJ

Pennington, NJ Yardley, PA

Yardley, PA Bensalem, PA

Bensalem, PA Borgota, Colombia

Borgota, Colombia Newtown, PA

Newtown, PA Burlington, NJ

Burlington, NJ Langhorne, PA

Langhorne, PA Princeton, NJ

Princeton, NJ Langhorne, PA

Langhorne, PA New York City, NY

New York City, NY New Hope, PA

New Hope, PA St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada

St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada Providenciales, Turks and Caicos Islands

Providenciales, Turks and Caicos Islands Willingboro, NJ

Willingboro, NJ Princeton, NJ

Princeton, NJ

Newark, NJ

Newark, NJ Trenton, NJ

Trenton, NJ Newtown, PA

Newtown, PA

Lawrence, NJ

Lawrence, NJ Seoul, South Korea

Seoul, South Korea

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Milwaukee, Wisconsin Pennington, NJ

Pennington, NJ Jenkintown, PA

Jenkintown, PA Ottsville, PA

Ottsville, PA Yardley, PA

Yardley, PA Providenciales, Turks and Caicos Islands

Providenciales, Turks and Caicos Islands Hopewell, NJ

Hopewell, NJ

Pottstown, PA

Pottstown, PA Playa del Carmen, Quintana Roo, México

Playa del Carmen, Quintana Roo, México Shanghai, China

Shanghai, China Beijing, China

Beijing, China Yardley, PA

Yardley, PA Beijing, China

Beijing, China Holland, PA

Holland, PA Langhorne, PA

Langhorne, PA Ringoes, NJ

Ringoes, NJ New Hope, PA

New Hope, PA Dreshner, PA

Dreshner, PA Yardley, PA

Yardley, PA Yardley, PA

Yardley, PA PA

PA

Xi’an, China

Xi’an, China

“Give Mother Nature a chance and she will do more honest teaching in a week than the textbook and the ritualized teacher can do in a year.”